It is now a truth that everyone recognizes: in Türkiye, constitutional debates never end; they constantly reproduce themselves, with attempts to solve existing problems by changing provisions in the Constitution under different headings. A role is attributed to the Constitution—one that neither it nor constitutional lawyers have ever claimed for it. It is as if Constitutions have invented certain concepts that have no reflection in society or historical events, and these inventions have somehow created various problems. The most important subject of these debates—and without doubt the greatest of the problems alleged to have been caused by the Constitution—is the Kurdish question. The Constitutions, which in some way determined the name of the nation as “Turk,” supposedly declared that the nation was Turkish without any foundation, thereby ignoring Kurds and people of other ethnic origins, and thus creating a problem. And the solution to this problem is said to require constitutional amendments: if Kurds are granted a constitutional status and if the name of the nation is defined not as “Turk” but as “of Türkiye” (Türkiyeli), then all problems will supposedly be resolved. Indeed, it is asserted that at the root of the problems lie the Constitutions of 1924, 1961, and 1982, adopted through undemocratic and illegitimate means, and that a return to the 1921 Constitution—presumably because of its highly democratic qualities—would, as if by a magic wand, serve as a balm to our wounds. Ah, these Constitutions…

Summarizing this approach—which has somehow become the dominant discourse today—was important for making sense of the relationship between national identity and Constitutions, which is the subject of this article. In fact, our issue is quite simple: What does the statement in Article 66 of the 1982 Constitution—“Everyone bound to the Turkish State through the bond of citizenship is a Turk”—actually mean? Is it an arbitrary expression written on a whim? Could it be changed from “Turk” to “of Türkiye” (Türkiyeli) or “Citizen of the Republic of Türkiye”? In short, can the change or non-change of this article be linked to the problems that exist in social life in one way or another?

First, it must be noted—according to some constitutional lawyers—that a constitution is the body of supreme rules that reflects the dominant ideology of the society in which it is applied, confers legitimacy upon the political power, and organizes that political power. In this view, Constitutions have three fundamental functions: to express and reinforce the fundamental principles and values on which society rests (an ideological manifesto); to legitimize political power (the normative cascade); and to organize political power (the map of power). It cannot be expected that Constitutions undertaking the first of these functions would be free of ideological content, and it cannot be overlooked that Constitutions are often described as the normative expression of a republican project. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that a Constitution which undertakes to express and reinforce the fundamental principles and values on which society is based would, within the framework of the nation-state system, contain and embrace the name of the sovereign nation.

As has often been pointed out recently, the fact that all Constitutions in the world repeatedly mention the name of the nation that holds sovereignty in that country is the natural result of this process. In summary, Constitutions must state and reiterate who the sovereign is—in these examples, the nation—that sovereignty belongs to it, and that in the state it owns, the map of power is drawn in the Constitution. In our own constitutional history, the fact that almost all of our Constitutions have done exactly this is nothing more than following this natural course. The 1924, 1961, and 1982 Constitutions all agree on designating everyone bound to the State of the Republic of Türkiye through the bond of citizenship as a “Turk.”

In the Law on the Fundamental Organization (Teşkilat-ı Esasiye Kanunu) proclaimed in 1921, no such expression was used, nor was any definition of citizenship made. The reason for this is that the 1921 Constitution was short, framework-based, and temporary. Let it be noted here that the claims—occasionally made—that the 1921 Constitution envisaged a federation or a state based on regions, that it was free of various impositions including, above all, the use of the name “Turk,” are absurd and have no basis in reality; but all these claims are the subject of another article. Nevertheless, it is significant that in the Treaty of Gümrü signed with Armenia in 1920, in the Ankara Agreement signed with France in 1921, and finally in the Armistice of Mudanya in 1922, which documented the victory in the war, various provisions referred to the army as the “Turkish army” (even in the Treaty of Istanbul signed after the 1897 Ottoman–Greek War this was the case) and to the Grand National Assembly as the “Turkish side.” This shows that the fact that the army and the state, and therefore the nation, were Turkish was not something invented by those who drafted the 1924 Constitution.

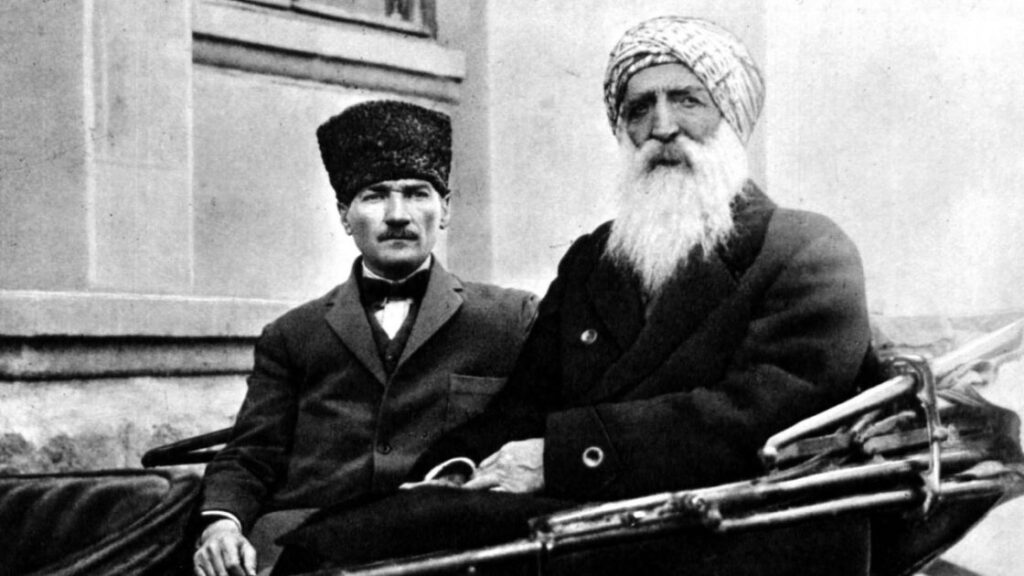

Contrary to the common narrative, the name of the nation was also discussed in the First Assembly convened in 1920. For example, on May 1, 1920—only eight days after the Grand National Assembly convened—when Kastamonu Deputy Yusuf Kemal Bey emphasized Turkishness in a debate on public health, this was met with an objection from Sivas Deputy Emir Pasha, who argued that the nation was not Turkish but an Islamic nation, and that the important thing was allegiance to the caliphate. Assembly President Mustafa Kemal Pasha, however, stated that the Assembly was not composed solely of Turks, solely of Circassians, or solely of Kurds, but of all Muslims, and that the borders set forth in the National Pact (Misak-ı Milli) had been determined according to this view; he concluded by saying there was no need to prolong the matter.

Following this early debate in the Grand National Assembly, discussions on national identity arose in various legislative proposals. In almost all of these debates, objections to the identity of Turkishness were raised. Yet, despite the majority of deputies being in favor of Turkishness, the prevailing view seems to have been that the discussion was postponed so as not to cause resentment during wartime. It would be useful to present to readers, directly copied, the records of these debates and the discussions they generated, as examined in the article titled “Debates on the Definition of the Nation in the Grand National Assembly during the Transition to the Nation-State and Their Reflections in the Laws.”

During the deliberations on the Village and Subdistrict Law (Köy ve Bucak Kanunu), debates arose regarding the definition of the nation. In the Assembly, opinions were expressed suggesting that it would be more appropriate to use the name “Turk” instead of “Ottoman.” Erzurum Deputy Hüseyin Avni Bey opposed the use of the word “Turk,” questioning what would happen to those who were not Turkish. Avni Bey argued that the term “of Türkiye” (Türkiyeli) would be more appropriate. Kastamonu Deputy Yusuf Kemal Bey, however, stated that he did not find the term Türkiyeli correct and proposed the use of the expression “Turkish citizen.” Malatya Deputy Lütfi Bey, diverging from these views, stated that he found the name “Ottoman” appropriate. Bilecik Deputy Necip Bey declared that the term “Ottoman” conflicted with the provisions of the Teşkilat-ı Esasiye (Constitution). He suggested that the term “citizen” would be more suitable. Besim Bey argued that the name “Ottoman” represented a family, and recommended preferring either the term “Turk” or “of Türkiye.” Diyarbakır Deputy Kadri Bey proposed that, instead of the term “Ottoman” appearing in Article 8, the expression “every individual belonging to the Government of the Grand National Assembly of Türkiye” be used; this proposal was subsequently accepted (TBMMZC, D:1, C:14, İ:105, pp. 70–72).

Dersim Deputy Feridun Fikri Bey, in a speech from the Assembly rostrum, expressed his observations on Turkishness. He stated that, in terms of blood, culture, tradition, and history, all the peoples of Anatolia were included in Turkishness. He emphasized that only the Turkish nation could be spoken of in the country, and that while there were individuals belonging to other ethnic groups, they had integrated into Turkish culture. Fikri Bey declared that once someone accepted Turkish culture and declared their Turkishness, it would be wrong not to consider that person a Turk (TBMMZC, D:1, C:4, İ:23, pp. 271–272).

Bitlis Deputy Yusuf Bey, while stating that he was of Kurdish descent, expressed that the Kurds had no aim of acting separately from the Turks. He said they regarded the Turks as their elder brothers and desired their happiness. He pointed out that the Kurds had trampled underfoot the rights and entitlements granted to them by the Treaty of Sèvres. He noted that throughout history, they had shed their blood alongside the Turks for the same cause, and therefore had no intention of separating (TBMMZC, D:1, C:24, İ:132, p. 353).

The tribal leaders of Aluçlu, İzoli, Bariçkan, Bükler, Cürdi, Deyükan, and Zeyve in the East expressed their desire to live together with the Turks in a telegram they sent to the Grand National Assembly. In the telegram, they remarked that the Kurds had realized that a small morsel is all too easy to swallow, emphasizing that their fate was shared with the Turks. Moreover, they stated that the Kurds did not consider those who sought to break away from Turkish unity to be of their own people. While expressing their loyalty to the Assembly, they also noted that they had no intention of pleading for mercy from the occupiers. They declared that the Kurds wanted peace within the borders set forth in the National Pact (Misak-ı Milli), and that they absolutely did not wish to hear of the Kurds being recognized as a separate ethnic group (TBMMZC, D:1, C:9, İ:8, p. 133).

Muş Deputy Abdülgani, Ahmet Hamdi, Bitlis Deputy Arif, Ali Vasıf, Siirt Deputy Necmettin, Diyarbakır Deputy Hamdi, Mardin Deputy Esat, and Van Deputy Hakkı Bey submitted a motion to the Assembly concerning the definition of the nation. In the motion, they emphasized that the Turk and the Kurd were one whole and expressed that the Kurds would not separate from Türkiye. They stated their belief that no state could break this unity. The deputies declared that the European states had no right to claim to defend the Kurds. They condemned the repetition of such initiatives despite the protests against them. They declared that the Kurds had fought alongside the Turks up to that day to end the occupation and that they were prepared to die for this cause in the future as well. In this regard, Erzurum Deputy Necati proposed that the speeches of Bitlis Deputy Yusuf Bey on this matter be published and announced to the world (TBMMZC, D:1, C:24, İ:132, p. 373).

Van Deputy Hakkı Bey also submitted another motion apart from the one mentioned above. In this motion, he stated that the Kurds had never considered themselves a group separate from the Turks throughout history, and that they would fight together with the Turks to the last drop of their blood to save the homeland from enemy occupation. Hakkı Bey further stated that there was no racial issue between these ethnic groups. Criticizing the attitude of Europeans on this matter, he emphasized that attempts to separate the Turk from the Kurd were delusional. He warned that such initiatives should not be allowed (TBMMZC, D:1, C:24, İ:132, p. 375).

Following these debates in the Grand National Assembly between 1920 and 1923, and before the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne and the proclamation of the Republic of Türkiye, Mustafa Kemal Pasha’s speech at the opening of the fourth legislative year of the Assembly signaled that the name of the sovereign nation in the newly to be established state had been determined. It should be noted that in this speech of March 1, 1923, he stressed that the delegates attending the Lausanne Conference had no other aim than to emphasize the Turkish nation’s right to live, like every civilized and capable nation. Mustafa Kemal Pasha continued as follows:

“The Turkish nation’s administrative, financial, economic, and legal independence, and its taking charge of its own life, is an eternal and natural right which should disturb no other nation. (Voices: Certainly!) Accepting such a natural truth is sufficient for the establishment of peace. But, as has been the case for years, whatever the outcome of persisting in any way—spiritually, practically, and in reality—in refusing to recognize the Turkish nation’s right to live, the Turkish nation accepts its independence with peace of mind and with a clear conscience, and will continue to uphold it. (Voices: Agreed!)”

Therefore, there should be no doubt that the Grand National Assembly of Türkiye engaged in debates on the concept of the nation both before and after the 1921 Constitution, and that these debates led to the conclusion that the sovereign nation in the Republic of Türkiye was the Turkish nation. This consensus also manifested itself during the drafting of the 1924 Constitution and was reflected in its citizenship article. Article 88 of the 1924 Constitution defined and named the nation as follows:

“The inhabitants of Türkiye, without distinction of religion or race, shall be called Turks in terms of citizenship.”

It should be noted that, during the adoption of this article and the 1924 Constitution, there were also questions and explanations in the Grand National Assembly concerning the expression “Turkishness.” The version of the article originally proposed, before being debated in the Assembly, read:

“The inhabitants of Türkiye, without distinction of religion or race, shall be called (Turks).”

Following the debates in the Assembly, the phrase “in terms of citizenship” was added to the article.

It should not go unnoticed that the bulk of these discussions concerned non-Muslims, rather than Muslims living in Türkiye. Some members of the Assembly considered it problematic, for various reasons, to grant non-Muslims the title of “Turk” and expressed the view that only those who had embraced Turkish culture (hars) could be regarded as Turks.

During the deliberations, Eskişehir Deputy Abdullah Azmi Efendi asked whether what was meant in the article was “nationality” (milliyet) or “citizenship” (tabiiyet). The rapporteur of the Teşkilat-ı Esasiye Committee, Çanakkale Deputy Celal Nuri Bey, replied to this question by saying, “It is citizenship, sir.” Azmi Efendi requested that the word “citizenship” be added alongside the term “foreigner” (ecnebi) in the article. Celal Nuri Bey responded that there was no need for the word “citizenship.”

Yozgat Deputy Ahmet Hamdi Bey, in a motion he submitted, proposed that Article 88 be amended to read:

“Those among the inhabitants of Türkiye who accept Turkish culture shall be called Turks.”

In reply to this motion, Celal Nuri Bey stated that the article did not determine nationality in an ethnographic sense. He referred the deputy to Article 39 of the Treaty of Lausanne, which stipulated that Turkish subjects belonging to non-Muslim minorities enjoyed the same civil and political rights as Muslims. For this reason, he said, it was not possible to add the word “culture” (hars) to the law (TBMMZC, D:2, C:8, İ:42, pp. 908–909).

For example, Hamdullah Suphi Bey held the view that a person who spoke a language other than Turkish and attended a school other than the state’s school could not be considered a Turk. Çanakkale Deputy Celal Nuri Bey also emphasized the importance of the concept of culture, asking the Assembly: “If we are not to call the non-Muslims living in the country Turks in legal terms, then what shall we call them?” In response to the suggestion “of Türkiye” (Türkiyeli), he stated that the expression Türkiyeli carried no particular meaning.

In summary, the citizenship clause—worded in Article 88 of the 1924 Constitution, later in Article 54 of the 1961 Constitution, and in Article 66 of the 1982 Constitution as “Everyone bound to the Turkish State through the bond of citizenship is a Turk”—did not emerge out of nowhere. It is the expression of a consensus reached as a result of the debates conducted by the intellectuals and deputies of the Turkish nation during the National Struggle and the subsequent process of building the nation-state. It is not based on the denial of Kurds, Circassians, Lazes, or people from any other ethnic origin living in Türkiye. One could even say that it would require ill intent to derive such a meaning from it. As stated at the beginning of this article, in almost every Constitution founded on the sovereignty of a nation, the name of that nation is mentioned and repeated as the sovereign, time and again.

Before concluding, it is worth recalling that the concept of the nation-state is expressed and regulated in many different ways in constitutional design. The most interesting example of this is found in the Constitution of Spain, which is considered a typical example of the “regional state” model. In Spain, while many nationalities—foremost among them the Catalans and the Basques—possess autonomous status, the distinction in the Constitution between the Spanish nation and the nationalities with autonomous regions is quite strict and clear. While the Spanish nation, including the peoples of the autonomous regions, is defined as a “nation,” the peoples—such as the Catalans and Basques—are defined as “nationalities.” The Spanish Constitutional Court has rejected interpretations claiming these two concepts are used equally, ruling instead that the nationalities must be understood as groups forming the Spanish Nation.

One could think of former CHP Deputy Birgül Ayman Güler’s statement, “The Turkish nation and the Kurdish nationality cannot be equal,” as an adaptation of the arrangements found in the Spanish Constitution to Türkiye. The accusations leveled against Birgül Ayman Güler after she made these statements are significant in showing how insufficient our background is for discussing such matters.

Therefore, arising from historical experience, the idea of equalization in Turkishness in terms of citizenship—enshrined in our Constitutions—has no legitimate basis for the attacks it faces today. To those who hide behind the slander and accusation that Article 66 gave rise to the Kurdish question and therefore to the PKK, one should recommend carefully examining whether, when explaining in their own words why they took to the mountains, in the PKK’s founding manifesto or in Öcalan’s book Defending a People, there is any reference to the Constitution. Anyone who studies these texts knows that the Kurds who acted together with the Turks during the War of Independence and even earlier in the Ottoman era are directly labeled as “collaborators” by Öcalan himself.

No one should presume to legitimize the PKK’s attacks on the Turkish nation—betraying national unity under the pretext of fighting for the Kurds—by invoking the Constitution. Just as no problem in Türkiye should be sought to be solved through amending the Constitution, neither should the solution to the PKK problem be sought in Article 66. Whatever anyone may say, the sovereign nation in the Republic of Türkiye is the Turkish nation. It should remain so—and it will remain so.