The phrase in the title belongs to Süleyman Demirel. In my opinion, this particular statement is one of his most valuable, though often dismissed as tautological or humorous and thus overlooked. Most politicians of Demirel’s generation, including Demirel himself, came from fields far removed from the social sciences. Nevertheless, they possessed high intellectual capacity — refined individuals who grounded their concerns for the country in deep and meaningful study. Above all, they knew history well and never made themselves look “ridiculous” when speaking of how something was won or lost.

Since the majority of our population in 1923 consisted of ethnic Turks, we named the nation-state we established — albeit belatedly compared to the West — “Turkey,” and referred to the founding people as the “Turkish nation.” In fact, since the 12th century, as Turkish populations began to dominate Anatolia, foreign sources started referring to Asia Minor with names derived from “Turk.” Had the majority of the population in 1923 been Bosniak, Albanian, or Kurdish, the name of the nation might well have reflected one of those identities instead. In all modern examples of nation-state and nation-building, the identity of the majority is adopted as the umbrella identity. This adoption does not occur because those bearing that name are the best, the most educated, or the most powerful — but because they are the most numerous. And building a nation by adding the minorities onto the base of the majority is the most rational approach. To put it more bluntly and clearly: the people who founded the Republic of Turkey were called “Turks” not because of their historical achievements, self-awareness, or international fame, but because they were the majority. Together with all the groups who, in difficult times and on difficult terrain, did not separate their fate from ours, we set out to build the Turkish nation — to construct it as a modern nation.

By 1923, it’s important to remember that those in power were cadres who had spent the majority of their lives immersed in warfare — in the Balkans, the Arab deserts, the Caucasus, and Anatolia. They had paid immense personal costs trying to hold on to these lands. There is no doubt that these individuals, who had retreated through war and managed to cling to Anatolia through relentless struggle, sought to establish a modern, strong, and unified state — one that could never again be invaded — by studying examples from around the world.

So, were there not people who were wronged or marginalized by the state during the founding period and afterward? Of course there were. But this was not done out of any ethnic motivation. In fact, if we go even further back in history, it becomes clear that ethnic motivation was virtually absent in the Turkish state tradition. During the Celali rebellions, which spanned over a century and a half, the state suppressed uprisings led by ethnic Turks. Looking at the locations of the Independence Tribunals (İstiklal Mahkemeleri) established during the National Struggle gives a sense of the ethnic backgrounds of those who were tried: Ankara, Konya, Isparta, Sivas, Kastamonu, Pozantı, Diyarbakır, Eskişehir, Samsun.

During the War of Independence, while we were fighting the occupying forces with every resource we could muster, we were also dealing with internal uprisings. Among our most pressing problems were rebellions that erupted in regions populated entirely by ethnic Turks — just like the later uprisings of Sheikh Said and Seyit Riza, which are still widely discussed today. We were also busy suppressing rebellions by segments of the Turkish population in places like Konya, Afyon, Yozgat and Bolu.

All of these uprisings — instigated by the British — delayed the success of our national struggle and led to the deaths, injuries, and immense suffering of tens of thousands of innocent people. In regions like Yozgat, the Kuva-yi Seyyare units, made up predominantly of Circassians, were responsible for suppressing the revolts. In other words, it was ethnic Circassians who put down the uprisings of ethnic Turks in the name of the Turkish national struggle. Similarly, the role of loyal ethnic Kurds in suppressing Kurdish uprisings should be understood in this context — much like today’s village guards (security volunteers), whose dignity is being frivolously targeted and undermined.

After the 1980 coup, the inhumane torture inflicted on leftist ethnic Kurds in Diyarbakır Prison was also being inflicted on right-wing detainees — most of whom were ethnic Turks — in Mamak. The state at that time did not care about anyone’s ethnicity when it denied the right to education for headscarved girls during the February 28 process. More recently, the ethnic backgrounds of the students arrested in Saraçhane were of no concern to either the state or the public.

The statement by the late Süleyman Demirel — often overshadowed by his witty persona, which was an expression of his intelligence — actually conveys a sharp truth: Not just our latest state founded in 1923, but the entire Turkish state tradition, regardless of whether it acted rightly or wrongly, has never maintained an ethnic double standard when it came to “crushing” what it perceived as a threat. It never has.

Undoubtedly, this reality does not ease the pain of those who have suffered, nor does it quell the demands of those who are seeking justice. As Demirel himself once famously said: “Yesterday is yesterday, today is today.” And he wasn’t wrong.

So, what does the current picture look like? If an ethnic Kurd is part of the ruling bloc, they can feel like an “equal citizen” — just like members of Hüda-Par do. But if you’re an ethnic Kurd in the opposition, achieving equal citizenship becomes much more difficult. In this sense, it is possible to understand the stance of DEM supporters. If the ongoing “opening process” ends up positioning DEM within the ruling bloc, they too may get to experience the privileges of “equal citizenship.”

Just like how, before 2016, supporters of Tayyip Erdoğan — while in opposition — were considered a national security threat and lived under the psychological weight of being pariahs in their own country, but after 2016, those same people (namely the MHP supporters), upon perceiving Erdoğan’s absence as the real national security threat, were suddenly promoted to the status of “equal citizens.”

So who is the “equal citizen” today? An ethnic Kurd affiliated with Hüda-Par or the AK Party, or an ethnic Turk who supports CHP, İYİ Party, or Zafer Party?

We should not shy away from admitting this: If a Turk is in power, they are an “equal citizen”; if they are in opposition, they are not. The exact same holds true for Kurds.

In truth, it is difficult to claim that anyone in this country — even those who belong to the ruling bloc — truly enjoys the rights and peace that come with modern “equal citizenship.” At best, there exists only the illusion of feeling equal.

When even ethnic Turks — who have carried the name “Turk” since ancient times and whose identity forms the foundation of the Constitution — can only feel like equal citizens depending on their proximity to power, I do not see it as a rational effort for ethnic Kurds or their political bloc to search for equality in carefully worded phrases inserted into a constitutional booklet.

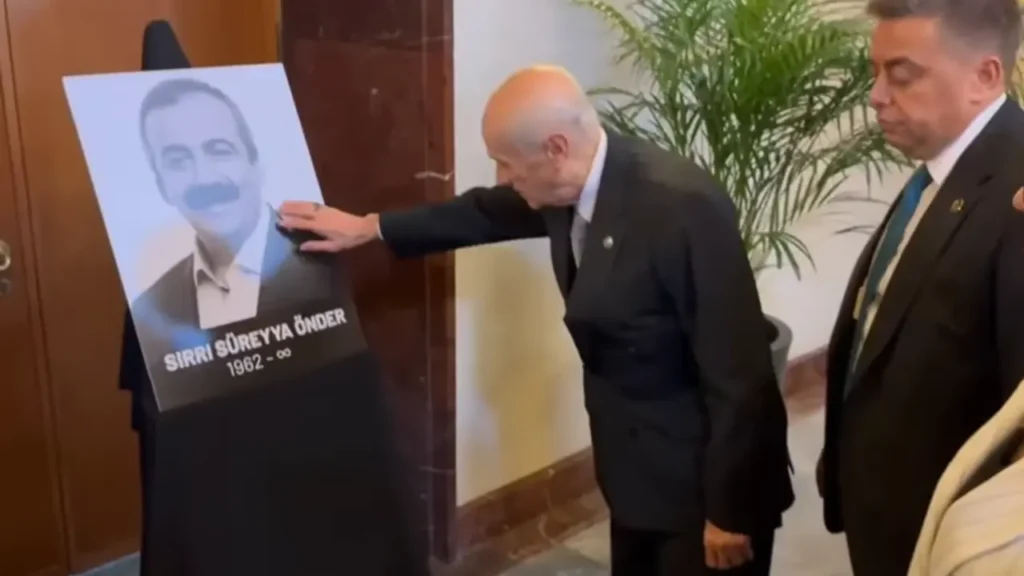

It may not be rational, but it is clearly an effort. And it’s also clear that the motivations behind this effort vary depending on the actors involved. For President Erdoğan, it’s one thing; for Bahçeli, it’s another; and for “PKK founding leader Abdullah Öcalan,” as Bahçeli puts it, it’s something else entirely.

To be honest, when evaluated in terms of motives, I believe that among all these actors, the only one likely to come out ahead from this process is President Erdoğan. The list of potential losers, on the other hand, could end up being quite long.